The problem with innovation, is that too little of it is ever returned as profit.

In most market sectors there is a strong dis-incentive to innovate. Companies are under commercial pressure to create products that will sell, rather than work to find new products that will genuinely benefit their customers. You see this at all scales, from international pharmaceutical companies down to young architects working in the private residential sector. We all fall into the trap of subservience to market demand.

At the very top, the construction industry is dominated by incumbent firms and established supply chains. Their modus operandi trickles down to small scale practice through workforce movements and a general pack instinct. It is my belief that there is little incentive to change or innovate the industry because it would be a difficult process to profit from, an idea that does not sit well with any firm mindful of their quarterly balance sheet.

Buildings take time. Learning the process of delivery within the commercial, practical and regulatory constraints is a never-ending battle, especially here in the UK. The length of time required to train in some ways hinders the architect's ability to think 'innovatively'. Because so much energy is expended to reach competence, why would they step outside this relative comfort? Amazing work is being done by brilliant architects, but they are having to answer to a raft of constraints that are not formally taught in architectural education and are therefore learnt later in the field.

How can we 'innovate' if we do not share the information and knowledge required to educate students in the delivery of real projects? This is where setups like Wiki-House are offering an alternative and exciting view, by sharing the tools and the designs to deliver a cheaper and better product that boosts supply but not costs. There is no denying, that this combination of pre-fabrication and information exchange is linking two different technologies to provide a new angle to housing provision in the UK.

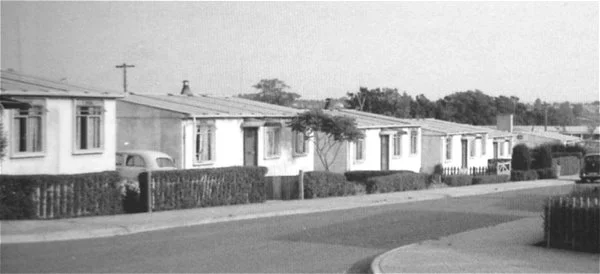

Due to the extensive bomb damage to housing and infrastructure in the Second World War, prefabricated structures were used on an industrial scale to overcome acute housing demand. I believe that this continued the homogenisation of the UK suburban home, started by the ribbon developments of the Inter-War period. Regional techniques were lost as an urgent need for supply, and an industrial method for delivery became available.

Larkhill Post-War prefabricated homes constructed in state of extreme housing need. Image: yeovilhistory.info

Another modern continuation of the prefab movement, is RSHP's research into pre-fab homes, including Y-House for the YMCA and their development in Mitcham. In our times, I do not believe that prefab will solve the housing shortage, and that the mechanisation of housing provision is not only generic, but it stands to do architects out of a job! The real battle to innovate, should be finding intelligent ways to respond to local challenges and local demand. Mass media and mass production have made us all too fond of the headline grabbing big solution to the big problem, which I think is wrong. We are capable of more.

Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners pilot prefab project in Mitcham, South London. Image: architectsjournal.co.uk

The problem we have in the UK, is land availability. The growth of our towns has been bound up in complex land policy since the Acts of Enclosure. While we can focus on the delivery of buildings quicker and at lower cost (as above), the process remains subservient to those who own the land upon which they wish to build. Historically this has created an irrational love for property ownership here in the UK, and the crazy rise in home value compared with inflation has fed the need to protect our interests by owning rather than renting. This is a situation very different to our European cousins, where stable rental markets allow people the choice to remain lifelong tenants. This inflated demand also means our homes are some of the smallest in Europe.

The question we should be asking, is how do we release land in the right places to build communities that people want to live in?

A further roadblock to innovating the housing market, is that property development is currently a huge earner for the national and local governments in the UK, where they partner with private sector developers to build-out sites using Joint Venture vehicles (often old inner city council estates or brown field). The coordination and expertise comes from the private sector, while the government receives a share of profits in the form of Community Infrastructure Levy or Section 106 agreements.

The late Sir Peter Hall championed a different local government structure in Freiburg, Germany, where brown field sites are purchased by the local authority and only then is it re-zoned as residential/commercial. When plots are later sold to developers it is the council that profits from the rise in land value, known as 'planning gain.' It should be noted that this precedent was only applied to large scale development where the local authority was involved in the purchase and development of sites.

The reason the system stays as it is in the UK, is because so many other government sectors are bleeding cash or lack the liquidity to balance their books on a regular basis. I argue that property development currently offsets loss-making sectors, like the NHS, which is far more contentious in the political context. This fuels the government's bullish attitudes to property development.

In conclusion, any new approach to large scale development in the UK would need to offer comparable increases to current government revenues in order to facilitate innovation in the construction industry, otherwise why would the government risk upsetting a market upon which they currently rely? New technologies and methods will continue to develop, and these should be celebrated. But until central policies re-align to allow them to flourish, these innovative solutions will not have the impact that they should.

Architects need to change their focus, away from pop-ups and prefabs, and set about creating homes and places as good as they can be, one project at a time. Every brief is different, so how can they all have the same answer?

References

Good Cities, Better Lives, Sir Peter Hall with Nicholas Falk, 2014, Routledge